A systems view of sin

OCTAVO Discussion 19

In Episode 19, Leonardo promised to meet Melzi in the studio garden, where he would answer his questions. The boy had been troubled by his master’s refusal to inflict pain on animals while designing weapons of war that would surely inflict pain on men. Leonardo listened and grew silent.

Then finally, “Your arrow has found its tender heel, my dear boy. Why must I—why must any man—harm others’ lives in order to live? I have no simple answer. All I will say is that we do what we must to survive. Virtue asks a price that only the powerful can afford, and even the powerful are loathe to pay it. Many would rather corrupt the less fortunate and increase their power than use it for virtuous ends.”

“Does this mean we are destined to live in sin?”

“Perhaps. I myself have no more stomach for war. I regret that I sought the patronage of men like Cesare. I was eager to apply my skills to the machinery of war, and take the money and learning it offered. I was weak. I lied to myself, saying that fewer people would die with more fearsome weaponry.”

As someone who was brought up a Roman Catholic, I’ve been thinking for many years about the nature of sin, and also how that word has fallen out of favor. Today, people are more likely to say a particular behavior is “inappropriate” rather than wrong, much less an actual sin. Maybe we prefer not to judge (lest we be judged), or maybe we’ve simply fallen into a postmodern torpor where every behavior can be excused under the right circumstances.

Let me put my cards on the table: I’m no longer a Catholic; I’m a devout atheist. But that doesn’t mean I don’t appreciate the moral lessons I absorbed during my 12 years in Catholic school. Or that I think religion is unimportant.

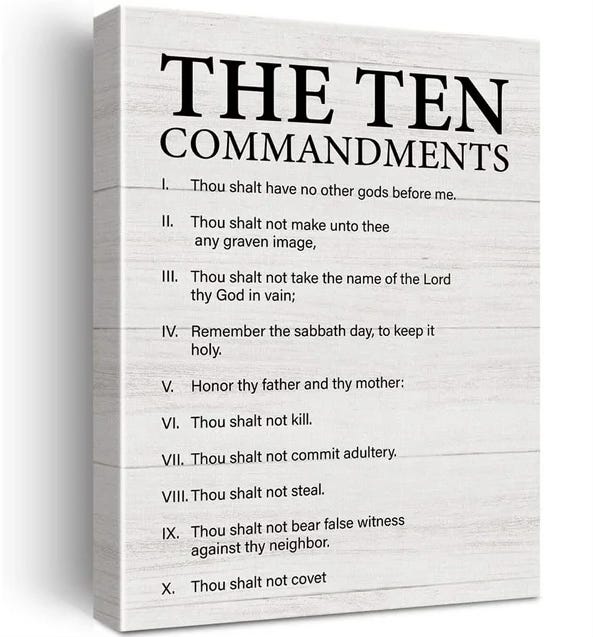

One of the great gifts of traditional religion has been the codification of right and wrong into a system that can easily be remembered, applied, and passed down from one generation to the next. The Ten Commandments is a good example of this. In fact, the rules of the world’s religions are not that different from each other, deriving from a single master principle that says we should treat others the way we ourselves would like to be treated. When we break any these sub-rules, or commandments, the infraction is called—or was called—a sin.

But what exactly makes a sin a sin? Can we better understand the nature of sin by looking at it through a more modern lens, such as systems thinking?

I think we can, and it might be our salvation. While the application of commandments may have been sufficient in a simpler age, in today’s era of societal complexity, digital misinformation, growing inequality, virtue signaling, political doublespeak, and the stubborn notion that wealth equals virtue, a handful of brittle rules isn’t going to cut it.

Leonardo viewed society and the natural world as both interconnected and dynamic. He realized the only way to understand how anything worked was to view it as part of a larger set of relationships, linkages, interdependencies, and interactions. These gave rise to the behavior of the system as a whole.

In Octavo, Melzi asks his master how it’s possible to be a good man in a world where the deck is stacked against virtue. Leonardo gives him an answer that situates personal morality in the larger context of an imperfect life:

“You shall learn in time that virtue is a right that must be earned through wisdom and strength. When we are young, we must take the work we are offered. When we are middle-aged, we must be strong enough to refuse it. And when we are old, we must repay the world for the damage we have caused in our youth.”

I’m pretty sure Leonardo never said these words. In fact, very few of his philosophical pronouncements have been recorded, so I was as surprised as anyone to see this come out of his mouth. One of the pleasures of writing fiction is that characters often say interesting things you would normally never think of saying yourself.

After considering morality for years, I now think there are few traditional sins that aren’t also bad behaviors from a systems point of view. The problem is, there are many more bad behaviors than commandments. For example, there’s no rule that says “Thou shalt not create financial derivatives,” and yet millions of people suffered irreparable damage from the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis.

Beyond the paywall I offer a non-religious definition for sin, including two gentle questions you can ask of anyone’s behavior, including your own. The Scarlett Files depends on subscriptions for its existence.