The view from taller shoulders

OCTAVO Discussion 3

Melzi’s manuscript begins with a (fictional) trip on horseback to Venice, where he and Leonardo are scheduled to meet with the printer Aldo Manuzio. Leonardo would only work with Aldo; the two had bonded over experimentation with advanced printing techniques. It’s the spring of 1508, and the air is still cold.

As they pass through Brescia, riding side by side, Leonardo reminisces about his golden years in the Florentine studio of Andrea del Verrocchio. In 1446,

“In 1466 I was apprenticed to Master Verrocchio,” he said, a smile playing across his lips. “About the same age as you when you were first apprenticed to me,” he added. “We had received a visit from Master Alberti. Though he was old in years, he was young in his passion for novelty. He had seen a mechanical printing press in Subiaco, and his thoughts had been racing ever since. He declared that printed books would soon revolutionize society.”

“‘Revolutionize!’ The word echoed in my 14-year-old ears like a trumpet blast.”

Although Leonardo had little schooling, he was lucky to land at one of the busiest and most successful studios in Florence. Verrocchio had the patronage of the Medici and an unerring eye for talent. He ended up mentoring some of the greatest painters and sculptors of the era, including Perugino, Ghirlandaio, Lippi, Botticelli. They all stood on the shoulders of Master Verrocchio.

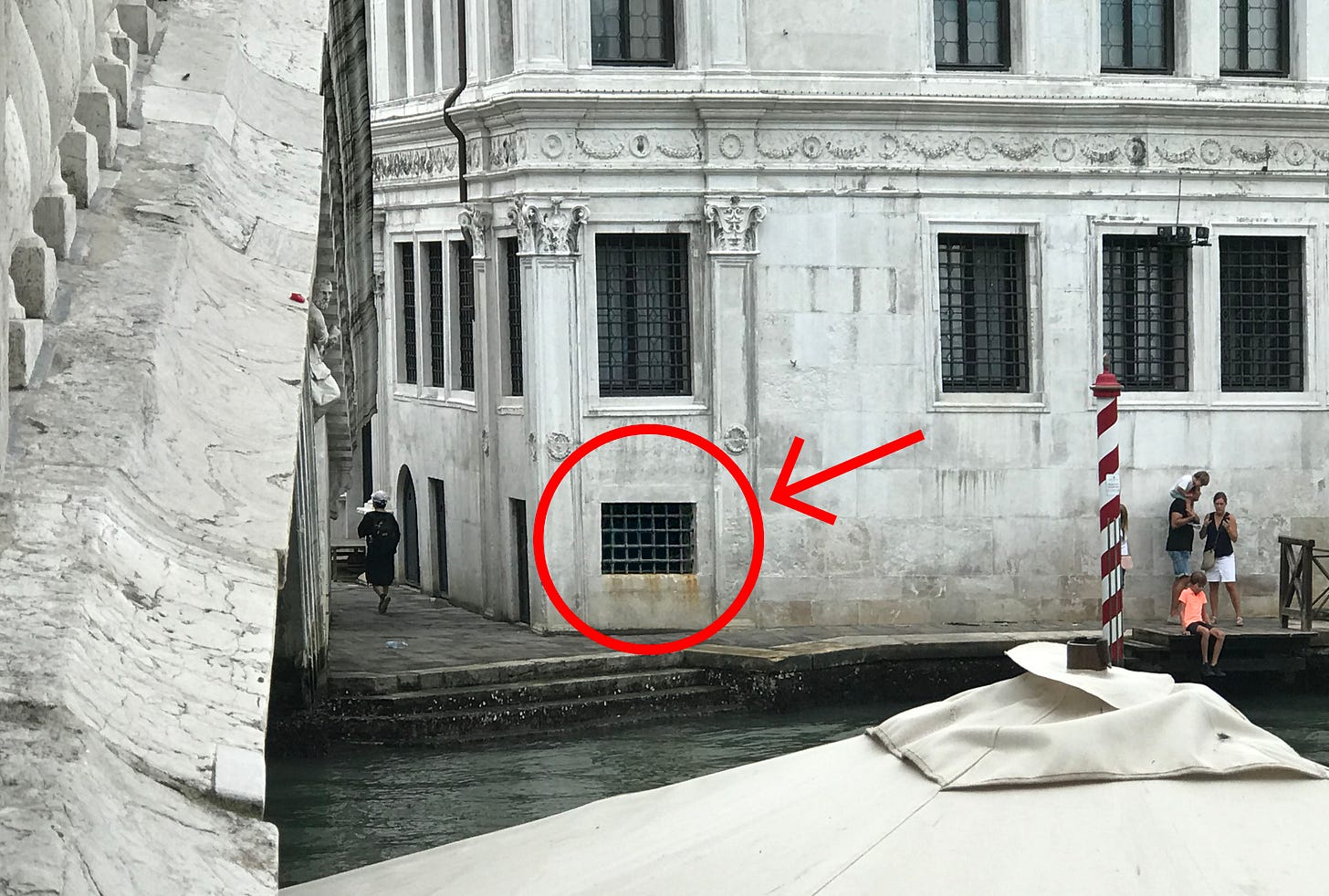

One of the joys of researching Octavo was taking a trip to Italy, together with my wife (and best editor), to take reference photos and talk with local historians. One of my favorite experts was Eleonora Penzo. She kindly allowed me to stand on her shoulders—metaphorically, of course, or I would have crushed her—allowing me a view of Venice few tourists will ever get. Passages like these are pure Eleonora:

We followed the porter past the debtors’ prison at the foot of the bridge. Hands reached through the low iron grilles. Voices cried for money, or food, or intercession with the authorities. The porter shouted back, saying they would not be in prison if their hands had calluses.

The Rialto was a swirl of activity as men unloaded vegetables, spices, and large jugs of wine, stacking and unstacking their crates on the quay. Seagulls screeched and squawked over scraps on the fish market floor. The heavenly scents of cinnamon, pepper, and saffron mingled with the foul smells of rotting flesh from the nearby abattoir.

Today she has an English-speaking tour-guide service. If you’d like to spend a fascinating few hours in Venice, reach out to her. Say ciao for me.

Book talk.

Eleonora offered a delightful bit of trivia I hadn’t come across in my other research. She said that during the early days of publishing in Venice, young boys strolled around the piazzas hawking books on sticks:

We followed the porter onto the Ruga San Giovanni, where the flow of pedestrians thickened and echoed noisily under corbeled overhangs. The street soon widened into a river of herringbone brick, where a number of booksellers had set up shop. Men delivered barrels of ink and reams of paper, and boys, younger than I, dangled books from poles, shouting titles that had been newly translated into Italian from Latin.

She noted that these wouldn’t have been complete books, just the title pages and a few signatures of text, not unlike the sample pages we get on Amazon today. I asked illustrator Anthony Smith to work up a sketch: