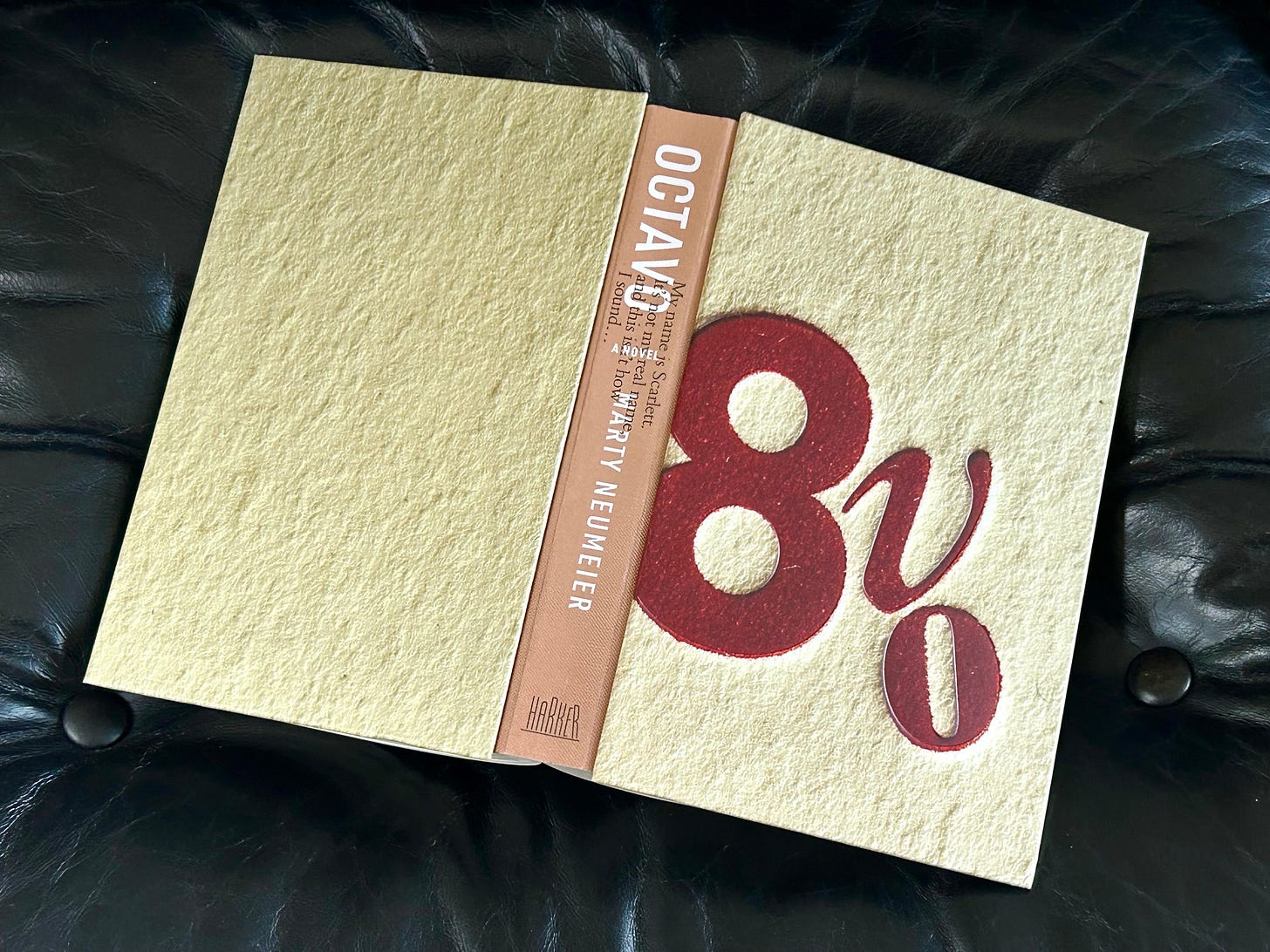

UPDATE: The commercial versions of OCTAVO are set to launch on October 14. The hardcover and softcover are uploaded to Amazon and Ingram; the audiobook is finished and set to go on Audible, Spotify, and other sites; the ebook is in final production; and the signed-and-numbered deluxe versions are going out to Founding subscribers now. (If you want one, there’s still time to upgrade.)

Today I’m freeing up earlier post from the Premium side. As a brand strategist, I’ve become fascinated by the challenge of publishing books in the digital era. I can confidently say that there’s no industry as competitive as today’s publishing industry. In fact, you could easily substitute the word “impossible” for “competitive.”

Is publishing dead?

You may have heard that about half the population reads one book a year. It’s unlikely that the other half reads ten or more. We’re too busy with work, too distracted by our screens, too addicted to other forms of cultural consumption. Even writers like me are complaining they have little time left over to read, what with all the demands of a creative life.

I thought we might start by discussing this idea, the idea that books are dead or dying—to poke it a bit, see if it’s true, see what it means for the future of society.

I wrote Octavo to take readers back a half millennium to when the book industry was new. The time was the Renaissance, the place Northern Italy. The Venice print shop of Aldo Manuzio had become the spark gap for a revolution—the shift from huge, heavy, handmade books to small, portable, mass-produced books, called octavos.

For the first time in history, a man who wasn’t a scholar or a clergyman could gain access to the greatest books of the age. What’s more, thanks to Aldo, he could read these books in plain Italian instead of the more scholarly Latin. Scientific ideas could now spread more quickly. It’s not too much to claim that the mass-production of portable books was the invention that launched the Industrial Age.

Book talk.

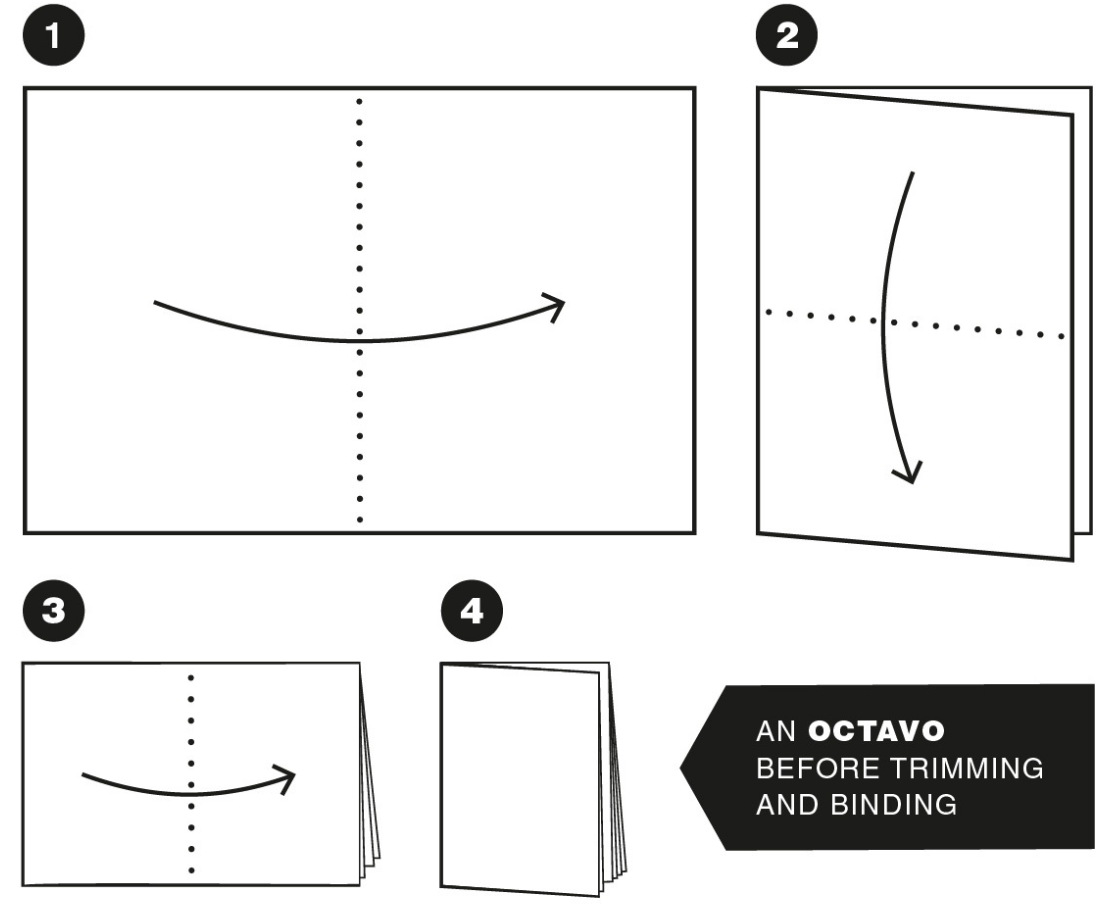

It’s about to get geeky, so buckle up. The word octavo, abbreviated 8vo, is Italian for octave, or eighth. In the printing business it proscribed a method of folding paper for a portable book. You take a large printed sheet and fold it in half, then fold it again, and then again, like this:

You end up with eight panels, or sixteen pages. You take the folded sheets, called signatures, and sew them together, trim them into a block, and bind the block between covers, called a case. After 500 years of mechanized printing, the octavo is still the standard folding pattern for books. Pull any casebound book from your shelf and count out eight leaves—that’s an octavo, or a signature.

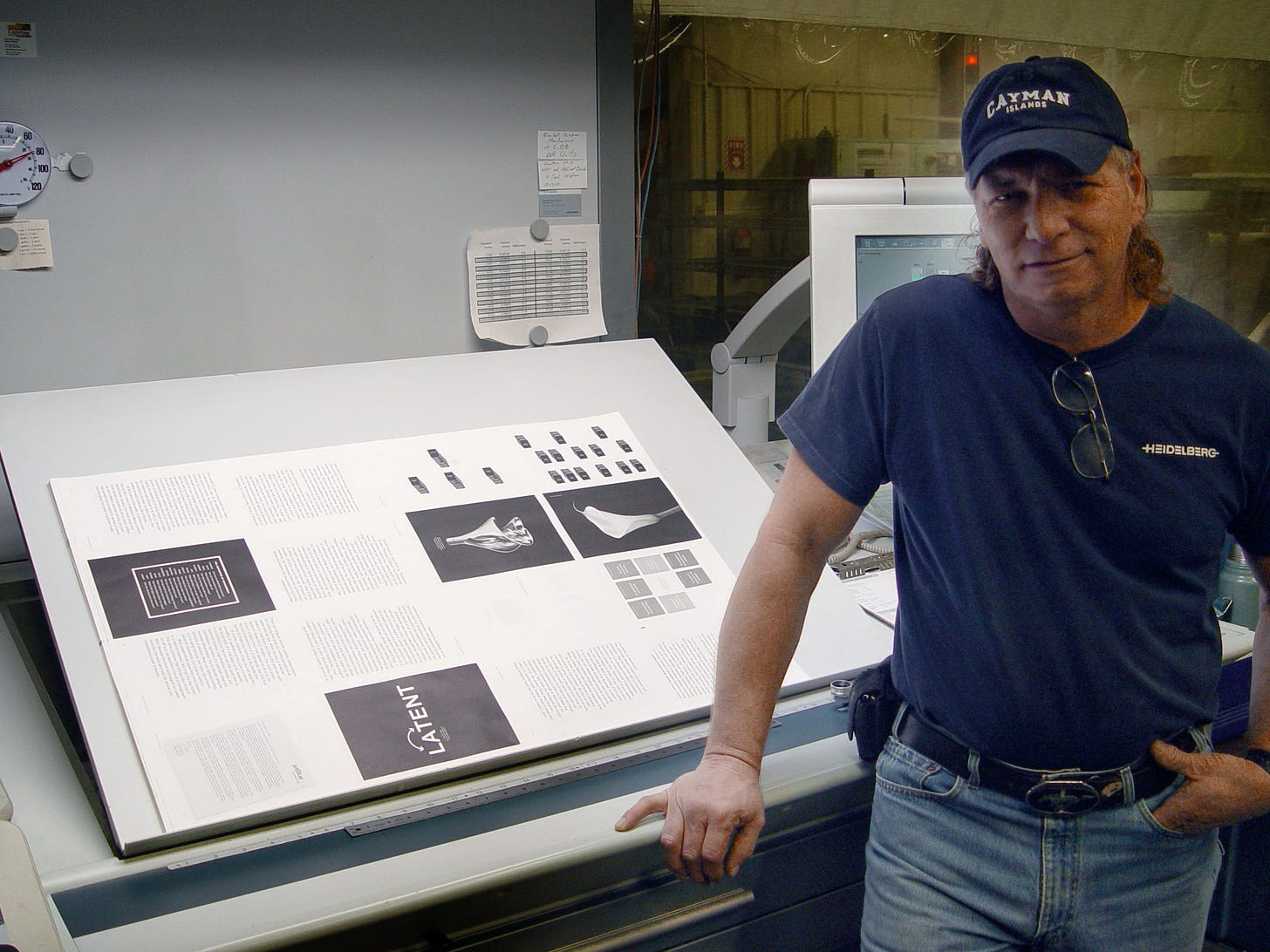

I know this because I was a graphic designer at a time when most communication pieces were still printed on a press. For big jobs the press was a large, heavy, multi-million-dollar Heidelburg or Miehle. The foremen would let you stand next to one of these iron monsters and supervise the ink density while your job was running. Not anymore. Printers keep the designers off the floor, on the principle that making tweaks and corrections plays havoc with their delivery schedules. Not to mention the patience of the press operators.

Octavo starts out with two characters trying to bully an editor into publishing a “found” manuscript. Each of the parties has a different motivation. The two women want to make the manuscript available to posterity. The editor wants to know if the women are worth a minute of his time, much less a publishing contract. After several conversations, the only thing he’s learned is that they’ve authenticated a rare portrait of Leonardo da Vinci. Interesting, for sure.

But how is that a book?

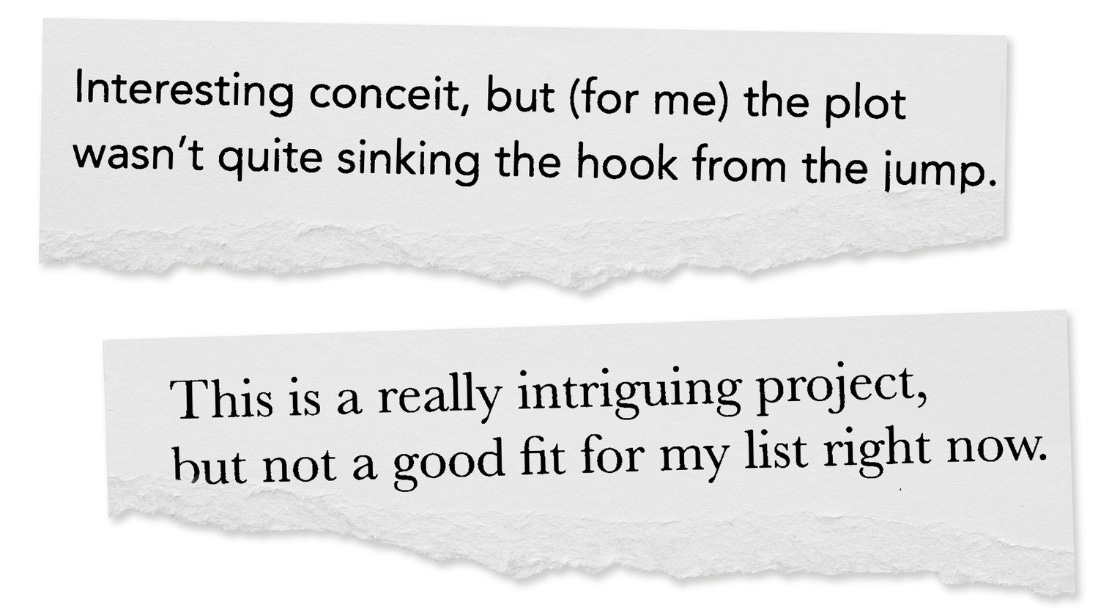

A few months ago, an editor from a prestigious publishing house rejected my manuscript for Octavo (as have many before), saying: “Interesting conceit, but (for me) the plot wasn’t quite sinking the hook from the jump.” A mixed metaphor, sure, but I like that phrase, “from the jump.” Every novelist knows that a story, especially a suspense novel, has to grab the reader’s attention from page one. I can handle a rejection along those lines, because it’s something I can fix. Much better than the anodyne brush-off: “Not a good fit for my list right now.”

Today all manuscripts, except for a tiny percentage, are not quite right for editors’ lists. Why? Because audiences read fewer books than ever, and the ones they do read are often written by celebrities. To put it plainly, celebrities sell better than authors.

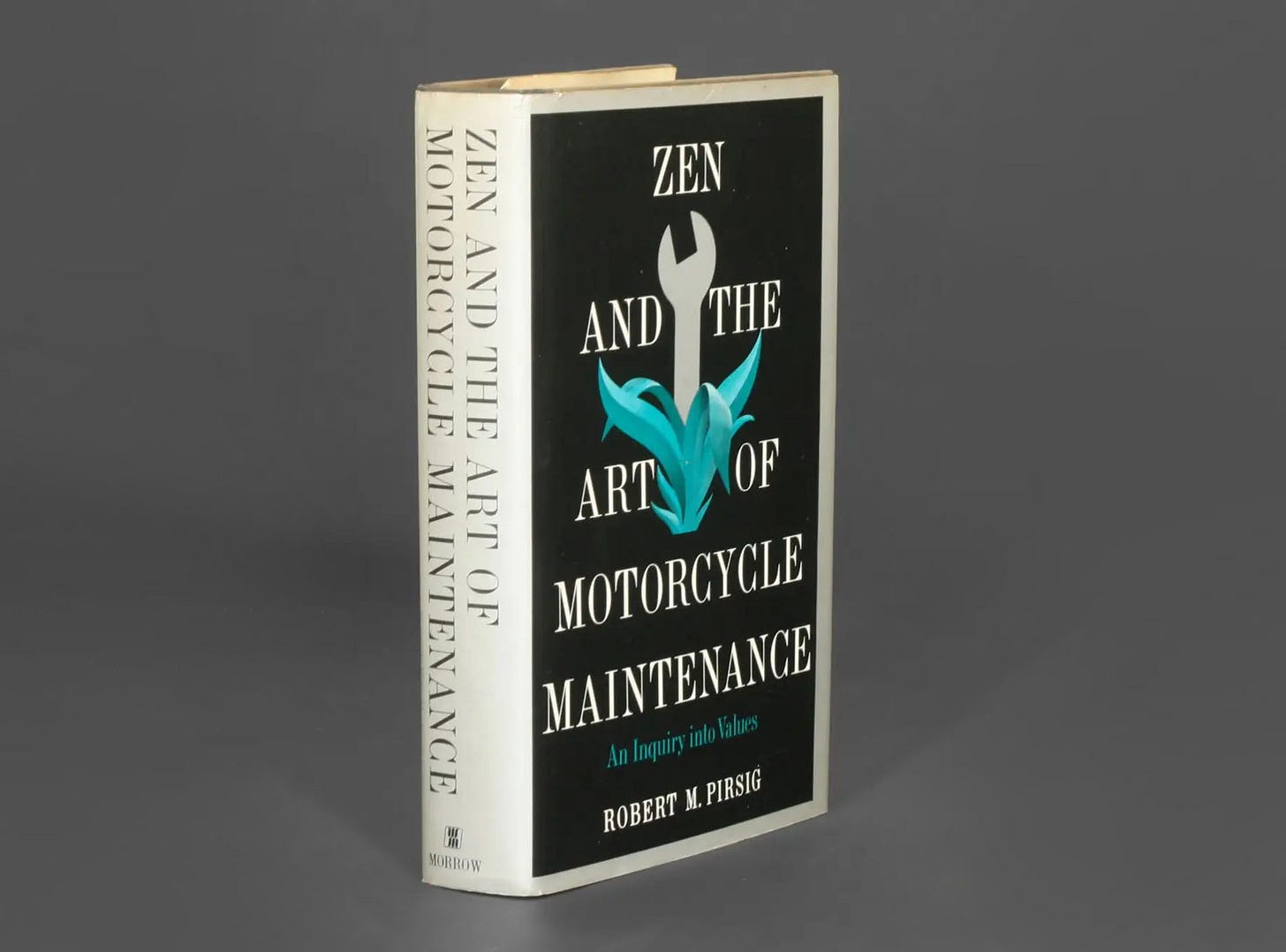

Rejections from publishers are not always a bad thing. The more the merrier, historically. A surprising number of the world’s great debut novels were rejected 30, 40, even a 100 times before taking their place as classics. Who knows—multiple rejections may be a leading indicator of greatness. One book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig, was rejected 121 times before finding a home at William Morrow (coincidentally, my first publisher). Fifty years later, I still can’t get Pirsig’s book out of my head, and I have zero interest in motorcycles.

As I piled up rejections for Octavo, I found myself increasingly drawn to indie publishing (as opposed to self-publishing). In the last few years, many of the missing pieces have fallen into place: print on demand, ebooks, free online serialization, bookstore distribution, audiobooks, a robust community of narrators, and, now, monetization through Substack.

The people at Amazon have made it easy to be an indie author, but they’ve also made it necessary. Traditional publishers can’t compete with the higher royalties, quicker time to market, and the freedom to color outside the genres. Like sunflowers, they’ve turned their eager faces toward the brightest stars in the firmament. The brightest of all is arguably Taylor Swift, and now even she’s planning to go indie. Traditional publishing, after 500 years of unbroken success, is officially broken.

Design talk.

My day job is teaching brand strategy to professionals. In our work sessions we often tackle the challenges of reimagining stuck industries—sectors of the economy that haven’t kept up with technology or changing customer needs. These have included air travel, higher education, corporate farming, personal transportation, and more. But the two industries that have given us the worst fits are publishing and retail bookstores. They’re so hidebound, so resistant to change, that we had to start with the most basic question of all.

What is a book, anyway?

The old answer: A book is a block of printed sheets bound between two covers. But the new answer? Nobody knows. Is it a printed octavo, as it has been for centuries? Or can it be an ebook, an audiobook, a serialized book, a streaming series, a video game, or a holographic experience? These are questions I’d like to explore in The Scarlett Files.

For now, let’s start smaller with innovation at the story level. Did you notice any unusual authorial choices in the first episode of Octavo? (You can read it here if haven’t had a chance.) I made a number of early decisions, but let me point out one that I might call “determinative.” It’s the decision to give Scarlett dysgraphia, a condition that makes it easier to communicate through voice recordings than emails. Why would I do that? Because a narrative delivered through voice files creates severe artistic limitations.

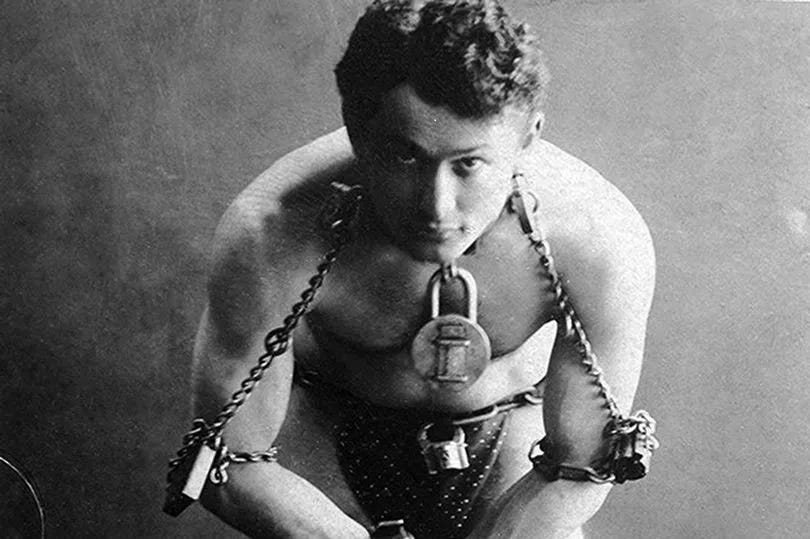

One thing I’ve learned as a designer is that limitation, not freedom, is the springboard of creativity. This particular limitation forces me to invent (or at least grapple with) a POV that might be called “first person live.” Scarlett and Artie are telling their story off the cuff and on the run. Third person would have given me more freedom, but I’m not looking for freedom. I’m looking for stricture, like a Houdini struggling to unlock his chains before he drowns.

“First person live” affords two special possibilities: it can make for a less-ordinary story form, called epistolary (think Dracula, Carrie, 86 Charing Cross Road), and it can make for a different sort of audiobook, in which the story is acted, not narrated. I imagined that the voices you’d hear in the audiobook would be the actual recordings transcribed for the book (if you’re willing squint your ears a little). This is the “interesting conceit” alluded to by the aforementioned editor.

A second decision was to ask more from the reader than a suspense novel typically does. Instead of following a single narrative from beginning to end, (spoiler alert!) you’ll have to follow two stories at once: an intricate Renaissance mystery and a fast-moving contemporary thriller. Both stories are packed with more geeky details than the guts of an iPhone.

Will most readers be up for this? Maybe, maybe not.

Back in the late 1960s, a radio interviewer asked John Lennon whether he believed the Beatles’ music was as good as the fans seemed to think it was. Lennon didn’t miss a beat. “I’m just the artist. It’s not for me to say, is it.” That struck me as so profound that I carried it with me ever since. It became the core tenet of my series of books on business and brand strategy: A brand is not what you say it is—it’s what they say it is.

Murder of the week.

All this talk about books and publishing leads to this week’s murder: bookshops.

Wait a minute, you say, bookshops are staging a comeback! And you’d be right. Barnes & Noble is battling back, and Anne Patchett’s bookshop Parnassus in Nashville does a good business, because, well...Anne Patchett. But the bookshop as we know it may be relic of a different time. Amazon and declining readership are seeing to that.

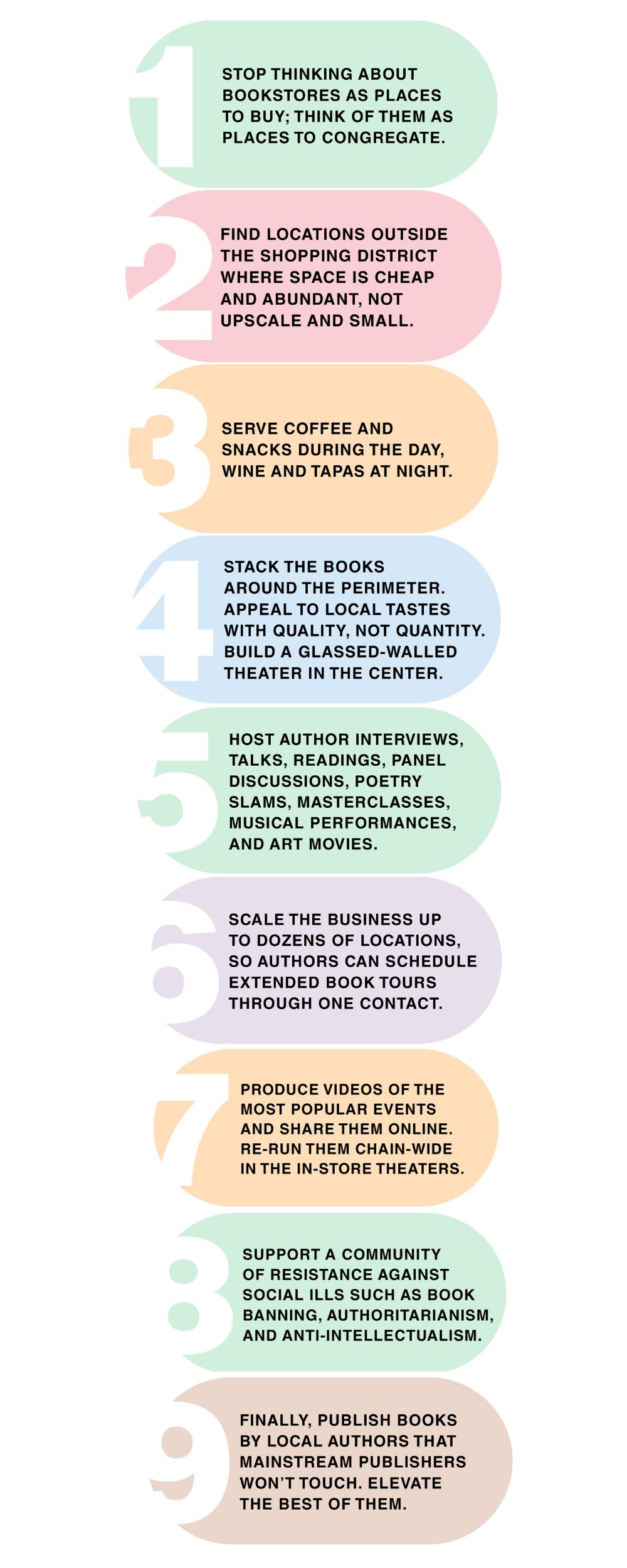

In a series of masterclasses that I run with my partner Andy Starr, we teach strategists and creatives how to reinvent organizations and industries through a customer lens. One of our recurring exercises is to disrupt (or rather resuscitate) the bookselling business. The ideas have been provocative. If I were to take the best ones and outline a new business model for selling books and reading, it might look something like this:

What emerges is an update to an earlier model in which bookshops were places to hang out and “talk treason.” Shops like Shakespeare & Company in Paris, or City Lights in San Francisco. The customer insight that stood out for me was this: Against an increasingly authoritarian background, resistors are ready to make the bookstore, not the Apple store, the center of progressive discourse.

While writing this it occurred to me that Substack is already hosting a virtual version of this concept. Who knows? Maybe someday it’ll be positioned to branch off in this direction. (The bookstores could be called—wait for it—The Stacks!) What do you think?

Your turn.

At this point I’d like to hear your thoughts. Did Octavo grab you from the jump, as the man said? Or was it more like a meh? And please tell me what brought you here in the first place. Are you an artist looking for inspiration? A reader who enjoys going behind the scenes? A writer with a book (or the next book) busting to get out? This is your chance to say hello to the group, and my chance to better match my discussions to your interests.

Wherever our journey goes, I want to you to know that I don’t take your company lightly. Your support is truly a gift to me, and to the rest of the group. See you next week!

I agree that the first 50 pages as the place where the crucial read/no-read decision will happen. But only IF you can get the reader past the first 10 pages. I hadn't thought of the Two-Jump Effect. I'd love to know if anyone read the first episode, liked it, and the went back to refresh their memory on the first episode. Let me know! Ive been known to do that with TV.

I've found through experience that there's a lot of storytelling in branding. It's not a great leap from brand to novels if you already know how to write. Now, as an indie author, I'm finding there can be a lot of branding in storytelling. If you believe as I do that a book isn't really a book without readers, then it's your responsibility to solve the whole problem, not just the writing part. It's all one thing.